In his 1990 talk “The Myth of the Standpoint” Karl Popper said:

...the correct method of critical discussion is: What are the consequences of our various competing theories? Can we accept them all? So this method consists in comparing different theories, or if you like, different standpoints, and it tries to find out which of the competing theories or standpoints has consequences that we find acceptable and which do not.

Karl Popper, The Myth of the Standpoint

I think that this passage describes not only the correct method of critical discussion, but also the way that intelligent minds work internally. Minds work by conjecturing ideas, working out the consequences of these ideas, and rejecting those ideas which seem, in light of the rest of the minds ideas, to have unacceptable consequences.

To implement artificial general intelligence, we need to figure out how to formalize this description to the point where it can be implemented on a computer. In trying to do this, several issues come up, including:

- What exactly are “ideas”? What do they consist of?

- How are the consequences of an idea determined?

- How does the mind determine which ideas are acceptable and which aren’t?

- How does the mind conjecture new ideas?

These four problems can be solved if we hypothesize that the mind behaves like a certain kind of mathematical system that I call a “computationally universal inference system”.

Modeling Inference

As a general model for deductive reasoning I’ll define “inference system” as an system composed of a rule of inference and a set of statements. A rule of inference, or inference rule, as a function that takes in a sequence of statements and returns a set of statements. A given inference rule is defined with respect to a certain “universe” of statements, a set of all possible statements that the rule of inference can act upon. Let an inference rule r, with respect to an universe U, be defined as r : 𝒯(U) → 𝒫(U). Here 𝒫(U) represents the powerset of U, the set of all subsets of U, while 𝒯(U) represents the set of all finite tuples, or sequences, of objects in U, or in other words 𝒯(U) = {(t1, …, tn)|n ≥ 0, ti ∈ U}.

An inference system composed of the rule r and statement set of S ⊂ U can be “expanded” by examining each tuple t of statements in S, computing r(t), and adding any new statements from r(t) to S. Mathematically, this process can be defined like so:

Er(S) denotes the “expansion” of S, and consists of all statements in S along with any statements that are implied, according to r, by a tuple in S. Er(S) does not describe all of the consequences of the the statements in S, but only those which are derivable in a single deductive step, i.e. a single application of the rule of inference. However, by iterative applying Er, we can eventually derive all of the consequences of the statements in S. Er2(S), or Er(Er(S)), is the set of statements derivable from S with at most 2 steps of deduction, Er3(S) is the set of statements derivable with at most 3 steps of deduction, and so on. Er∞(S) denotes the limit of iterated applications of Er on S and is the set of statements derivable from S with any number of deductive steps (depending on the statements in S, Er∞(S) may be infinite, or in other words there might be an infinite number of statements derivable from S).

If we imagine a mind as an inference system, such that each idea in the mind is a statement in the inference system, we can see how a mind would work out the consequences of its ideas. A mind would simply have to iterate over the set of sequences of ideas within it, compute the value of some inference rule r for each sequence, and add any new resulting ideas to its set of ideas (meaning that they can be used in input sequences to r in later iterations).

Computationally Universal Inference Systems

If intelligent minds work like inference systems, what kind of inference rule might they use? From a critical rationalist perspective it might seem implausible that a mind could work according to a single, fixed rule of inference. Surely the means by which a mind determines the consequences of an idea must themselves be considered fallible, and be open to change.

Thankfully, this concern can be assuaged by adopting a special kind of inference rule: one which can emulate the behavior of any other inference rule that we might want to consider. Specifically, what we want is a computationally universal inference rule: an inference rule that can emulate the behavior of any other computable inference rule if it is provided with the right set of statements. With such a rule, the way that the mind interprets ideas can be changed simply by changing the set of ideas itself, and the universality of the rule ensures that there is no restriction on the ways that a mind can interpret its ideas.

As an example of a computationally universal inference system, consider the universe B which consists of all finite bit strings (sequences of 0s and 1s). An inference rule over this universe is a function that maps from sequences of bitstrings to sets of bitstrings, i.e. from 𝒯(B) to 𝒫(B). For an inference rule to be computationally universal with respect to this universe, it needs to be able to emulate the behavior of any of inference rule on the universe that is computable, i.e. any computable function that maps from sequences of bitstrings to sets of bitstrings.

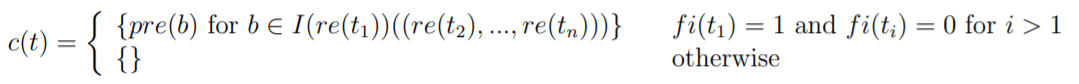

We can construct a computationally universal inference rule by utilizing a universal programming language. Let P be a set of programs in some programming language that each represent a function from 𝒯(B) to 𝒫(B), and let the language be powerful enough such that there is at least one program in P corresponding to each computable function of this form. Additionally, assume for now that P and B are disjoint (non-overlapping) sets, meaning programs in our language are expressed as something other than bitstrings. Let I be a function that interprets programs in P, such that I(p) for some p ∈ P denotes the function implemented by p. We can then define our computationally inference rule c on the universe B ∪ P. For a tuple t = (t1, …, tn) of elements in B ∪ P, c(t) is defined as:

In other words, if the sequence provided to c consists of a program in P followed by some number of bitstrings, c evaluates the program and passes the bitstrings to it as inputs, and returns whatever the program outputs. Otherwise, c simply returns the empty set.

We know that c is a computationally universal inference rule because for any computable inference rule f : 𝒯(B) → 𝒫(B), there will be some program p ∈ P that represents f, or in other words some p such that I(p) = f. An inference system that uses c as its inference rule can therefore emulate f by including p in its statement set. This emulation can be understood as follows: For a set of statements S, Ef∞(S) = Er∞(S ∪ {p})-{p}. In other words, you can emulate the behavior of f on a statement set S by using c on the statement set consisting of the elements of S along with a program which implements f. The result of c when used on this expanded set will be identical to the results of f on S, except for the presence of the single statement describing the program.

The fact that we have to expand our universe from B to B ∪ P might make this example of a computationally universal inference rule seem unsatisfying or inelegant, but thankfully there is a similar way to construct a computationally universal inference rule that doesn’t require expanding the universe beyond B. Before, we assumed that P and B were disjoint, meaning that programs in our programming language were expressed as something other than bitstrings. Getting rid of this assumption, and allowing our programs to be expressed as bitstrings, lets us define a computationally universal inference system that works entirely within the universe B.

To demonstrate how this could work, let us define a new inference rule cB, which makes use of a new function IB for interpreting bitstrings as functions (such that, for each computable function f : 𝒯(B) → 𝒫(B), there is at least one bitstring b ∈ B such that IB(b) = f). cB will work much like c, but rather than distinguishing statements representing programs from other statements by having them belong to a different set, statements representing programs will start with 1 while all other statements will start with 0. Whenever a new statement is derived from prior statements, it will be prefixed with a 0 to indicate that it should not be interpreted as a program. If we let fi(b) denote the first bit in a bitstring b, re(b) denote the rest of the bits in b, and pre(b) denote the bitstring consisting of 0 followed by the bits in b, we can precisely define cB like so:

General Intelligence

What significance do computationally universal inference systems have for AGI? The key feature of a computationally universal inference system is that, given the right set of statements, it can emulate the behavior of any other computable inference system. General Intelligence, in this view, can be thought of as an evolutionary search process over the space of all computable inference systems, or in other words, all possible ways of deriving conclusions from premises. And because a computationally universal inference system can can emulate any other computable inference system, we can think of this search simply as a search over the space of possible sets of statements within any arbitrary computationally universal inference system.

I said before that I think the mind behaves like an inference system, but this explanation is clearly missing at least a few elements. Inference systems may describe how mind performs deduction, how it derives the implications of its ideas, but that isn’t all that minds do. Minds sometimes come up with entirely new ideas that don’t deductively follow from any of their existing ideas, and they also sometimes realize that some of their ideas are wrong, and reject them. Thankfully, we can extend the framework I’ve described to account for these properties.

Conjecture is the process by which a mind guesses new ideas that don’t follow from its existing ideas. I guess that this process of conjecturing new ideas works by blindly varying existing ideas, just as genetic mutation creates new genes by blindly varying existing genes. To implement conjecture, we can take inspiration from genetic algorithms, a class of optimization algorithms that mimic the logic of genetic evolution. Genetic algorithms attempt to solve a problem by evolving a population of potential solutions, each of which are represented as some kind of mathematical object. Bitstrings are a common choice for representing solutions in these algorithms, so many procedures for blindly generating new bitstrings by varying existing bitstrings have already been proposed and studied. One basic example point mutation, which works by flipping a random bit in an existing bitstring to create a new one. Another very powerful procedure is crossover, which consists of taking some number of bits from the start of one string, some number of bits from the end of another string, and concatenating them to create a new bitstring. We can adopt these procedures, or others like them, as ways of generating new ideas by mutating existing ideas.

So, to model conjecture, we can say that a mind has some built-in procedure for conjecturing new ideas that it occasionally invokes. The ideas created by this procedure would be added to the mind’s set of ideas/statements, and the mind would then go on to evaluate the consequences of these ideas (in the context of the rest of the mind’s ideas).

In addition to creating new ideas via conjecture and deduction, minds also narrow down their sets of ideas through criticism. Minds perform criticism by looking for contradictions between the ideas within them. When a set of ideas is found to entail a contradiction, the mind knows that not all of the ideas in the set can be true, so it knows it needs to reject at least one of them. In other words, a contradiction shows the mind that it cannot simultaneously accept all of the ideas involved in the contradiction.

Formalizing Conjecture and Criticism

Since there are many possible procedures for generating conjectures, I’ll use a general formalism that can encapsulate any such procedure: for a statement universe U, we can represent a procedure for generating conjectures as a function that receives a subset of U and returns a probability distribution over U. The process of generating a new conjecture can be understood as taking a sample from the probability distribution that the function returns given the current set of ideas in the mind.

As I said before, criticism involves looking for contradictions between ideas. To describe this formally we need to first define what it means for two ideas to be contradictory. A contradiction exists when a mind simultaneous contains two ideas that are exact logical opposites, i.e. when it contains an idea of the form “X is true” and an idea of the form “X is false”. To recognize when a mind contains a pair of opposite ideas we can define an “opposition function” o(s) : U → U which, for any statement s in a universe U, returns the opposite of s. This function should obviously have the property that, for any statement s ∈ U, o(o(s)) = s, i.e. any statement is the opposite of its opposite. Given such a function, we can say that a mind contains a contradiction whenever it has contains two ideas s1 and s2 such that o(s1) = s2 (and therefore o(s2) = s1).

To give an example of an opposition function, we can again imagine a mind that represents ideas as bitstrings. We could then define an opposition function that says two bitstrings are opposites if and only if they are of the same length and share all the same bits except for the first bit. For instance, the opposite of a statement 1101 would be 0101. In this case you can interpret the first bit in a statement as being a “truth flag” where 1 represents true and 0 represents false, while the rest of the statement represents the “content” of the statement. So the statement 1101 reads as “101 is true” while the statement 0101 reads as “101 is false”. Of course, this opposition function isn’t the only one that you could define for a universe consisting of bitstrings. We could just as easily define two statements to be opposites when they are the same length and all they share all but the last bit. I guess that the choice of opposition functions doesn’t really matter; any will do. Whatever opposition function we choose, the mind should evolve towards a set of ideas that is self-consistent with respect to that function, so which one we choose is unimportant.

With all this in mind, we can define a mind as a 5-tuple M = {U, S, r, c, o}. U is a the universe of ideas that the mind can possibly consider. S is the set of ideas that the mind currently contains, and is a subset of U. r is a computationally universal inference rule that describes how the mind derives the implications of its ideas. c is a conjecture function, which takes in a set of ideas and returns a probability distribution over U, and describes how the mind conjectures new ideas. o is an opposition function that returns the opposite idea for any given idea in U, and it describes how the mind recognizes contradictions.

The mind evolves over time by updating S based on r, c, and o. This evolution works via an iterative process, each step of which involves creating a new set of ideas S′ based on the mind’s current set of ideas S. The first step of this process is to conjecture a new idea i by sampling c(S). At this point we have a new set of ideas S+ = S ∪ {i}. After creating this new idea the mind attempts to resolve any contradictions entailed by the ideas in S+. To do this the mind computes Er∞(S+), i.e. it works out the consequences of all the ideas within it (including the newly conjectured idea i). It then looks to see if there are any contradictions among the consequences of its ideas, i.e. if Er∞(S+) contains any pair of ideas s1 and s2 such that o(s1) = s2. If Er∞(S+) contains no such contradictory ideas, that means that the mind can accept all of the ideas in S+ without issue, so it doesn’t need to get rid of any ideas in S+, and S′ = S+. However, if the mind does contain a contradiction, then it may discard one or more ideas within it, meaning that S′ ⊂ S+. In this case, the set S′ should chosen in such a way that Er∞(S′) no longer contains any pair of ideas s1 and s2 such that o(s1) = s2.

Missing Pieces

In the quote I referenced at the beginning of this post, Popper argued that critical discussion consists of comparing the consequences of various theories and trying to find out which have acceptable consequences and which do not. With the model of the mind that I have outlined we can see that it isn’t only critical discussion that works this way, but all critical thought. We can see how a mind introduces new theories, how it works out the consequences of those theories, and how it recognizes when some of its ideas are mutually unacceptable. Unfortunately, this theory doesn’t yet offer a complete description of general intelligence, because there is at least one big missing piece.

The biggest missing piece in this theory is an answer to the question: what exactly the mind does when it finds that some of its ideas are mutually unacceptable? I’ve said that when a mind finds a contradiction it may discard one or more ideas to resolve the contradiction, but which ideas should it remove? In mathematical terms, when the mind finds, during a step of evolution, that Er∞(S+) contains a contradiction, how exactly does it determine which ideas in S+ to include in S′ and which to exclude? The issue here is not simply how to find a way to resolve the contradiction, i.e. how to find a set S′ such that Er∞(S′) contains no contradictions, as that much is trivial: we can always solve it by simply letting S′ be the empty set. The problem is instead how to ensure that when a mind does choose a subset of S+ as the value for S′, it chooses it in such a way that it doesn’t let go of any valuable explanatory content. Choosing the empty set for S′ clearly doesn’t satisfy this criterion, as it amounts to discarding every idea in the mind, and thus it means letting go of all the explanatory content that the mind has accumulated. I haven’t yet come up with any method for choosing S′ that satisfies this criterion, and I think that finding one that does is the most important problem left to be solved in the field of AGI.

Tags: Epistemology, AGI, CTP Theory, Conjectural Inference Theory