The Problem with Randomness

Games that make use of randomness often suffer from the problem of luck deciding matches. If the rolls land in your favor, you might get more resources, or your attacks may land more frequently, making the game easier. If the rolls don't land in your favor, you may feel starved for resources, or miss more attacks than you should have. While the law of large numbers tells us that disparities caused by luck decrease as the number of rolls in a match increases, having so many rolls is impractical for many designs.

Keith Burgun's article Three Types of Bad Randomness, and One Good One suggests a solution to this problem. Keith calls it "uniform randomness", contrasting it with "variable randomness". Uniform randomness "controls for the 'overall value' given out over the course of a match", which guarantees that the player receives a fair outcome. Variable randomness, the more common of the two types, doesn't impose any control on the overall value, and thus doesn't make any guarantees about fairness.

Keith suggests one way of making randomness more fair: "imagine in some kind of tactics game, you roll a six-sided die to deal 1 to 6 damage. This is variable randomness, but we can convert it to uniform randomness by having a deck of six cards numbered 1 to 6, and you draw from that deck (and reshuffle when necessary) to deal damage. It's still random, but now you are guaranteed a 6 (and every other number) per every six attacks. And overall, the amount of value you get from match to match is, well, pretty uniform."

This suggestion, of replacing dice-like randomness with deck-like randomness, clearly accomplishes its goal of reducing the variation in the "overall value" of the rolls. However, it does have some unfortunate properties. In this article, I want to talk about the pros and cons of the deck system as compared to the dice system, and introduce some alternative systems for ensuring fair randomness.

Balancing Unpredictability and Fairness

The purpose of random rolls in strategy games, broadly speaking, is to provide unpredictability, to disrupt the player's ability to plan for the future. However, as Ketih points out, we also want random rolls to be fair. Therefore, there are two properties that a good randomness system should have: unpredictability and fairness.

Unfortunately, there seems to be a tradeoff between these two properties. Consider two systems, which I'll refer to from now on as the “dice system" and the “deck system". In the dice system, the result of each sample (here I use the term “sample" to mean one instance of taking a number from system that produces numbers in a randomized way) is fully independent of the results of the previous samples. Each sample is chosen by drawing from a uniform distribution over all possible values that the system can produce, as though each sample were the result of a dice roll. In the deck system, there is a “deck" containing all possible values that the system can produce. During each sample, a value is taken randomly from the deck, and then removed from the deck. Once the deck is empty, it is refilled with all of its original contents.

How do these two systems measure up to the criteria of unpredictability and fairness?

The dice system, as mentioned before, is a very unfair system. However, it does do a great job of being unpredictable. In fact, it is as unpredictable as any system can possibly be.

The deck system, on the other, is as fair as any system can possibly be. To demonstrate this, consider a deck system with n possible values. After n samples, each sample will have been chosen exactly once, because no value can be chosen for a second time until all values have been chosen at least once. And after n * 2 samples, each sample will have been chosen exactly twice, because no value can be chosen thrice until all values have been chosen twice. Similarly, for any constant m, each sample will have been chosen exactly m times after n * m samples. When the number of samples isn't a multiple of n, some values will have been chosen more frequently than others, but that is unavoidable: there is no other system that can avoid this problem either. And even when the number of samples isn't a multiple of n, no value will have been chosen more than once more than any other value, because no value can be chosen x + 1 times until all values have been chosen at least x times.

While the deck system is great for fairness, it isn't as unpredictable as the dice system. Consider a deck system with 5 possible values. Once 4 samples have been taken from the system, there is only one possible value that the next sample can have. This means that, if you know how the randomness system works, and you pay attention to the first four samples, you can predict the value of the fifth sample with certainty. Similarly, you can predict the tenth sample with certainty if you pay attention to the sixth through ninth samples, and so on for the fifteenth sample, and the twentieth, etc. And even when you aren't at a sample that's a multiple of 5, you can narrow down the possibilities for the next sample and thus make the system more predictable. For instance, the first sample has 5 possible values, but once you've seen the value of the first sample, you know that there are only 4 possible values for the second sample, and after the second sample there are only 3 possible values for the third, etc. A dice system with 5 possible values, on the other hand, has 5 possible values for each and every sample, and is thus much less predictable.

So, the dice system is optimally unpredictable while being very unfair, and the deck system is optimally fair while being very predictable. Ideally, we'd like to find a system which is both fair, and unpredictable.

Making the Deck System Less Predictable

There are a few ways that you could change the deck system to make it less predictable. For one, you could have more than one copy of each value present in the deck. Since you would reach the end of the deck less frequently, you would less frequently end up in a situation where a roll is very predictable.

Another change you could make to the deck system would be to refill the deck before it is entirely empty. For instance, if you had a deck system with 10 possible output values, you would normally refill the deck after 10 samples, after all values have been chosen. Instead you could refill the deck when there are, say, 3 values that haven't yet been chosen, after 7 samples. After the 7th sample was taken, the deck would contain 13 values: one of each possible value, and a second copy of the three that hadn't yet been chosen. With this modification, the deck will never have only one card left, so the next sample will never be perfectly predictable.

Each of these modifications makes the deck system less predictable, but they do come at the cost of fairness. As I explained before, the unmodified deck system is as fair as a system can possibly be, because at any given time, no value will have been chosen more than once more than any other value. Both of the modifications that I suggested ruin this property, and so they aren't guaranteed to be as fair as an unmodified deck.

Making the Dice System More Fair

Just as there are ways to modify the deck system to make it less predictable, there is a way to modify the dice system to make it more fair. The problem with the deck system is that once a value is chosen, it is just as likely to be chosen during the next sample. The way so solve this problem is to modify the system such that, whenever a value is chosen, we decrease the probability of choosing that same value in the future (and then adjust all the probabilities upward so that they still sum to 1).

Since a value's probability decreases whenever it is chosen, you will be less likely to get the same value very many times, so the system will be more fair. However, because you know that you are less likely to get a value that you've seen recently, the system is also more predictable than a normal dice system.

Measuring Fairness and Unpredictability

Note: So far, I have avoided using mathematical language wherever possible, to make this article as accessible as possible. However, in the rest of this article, I'm going to get into some more nitty-gritty mathematical stuff. If you aren't interested in that you can skip to the Conclusion section to get a summary of my recommendations.

It's easy to compare the properties of the unmodified dice and deck systems, because they represent the poles of the fairness/unpredictability trade-off. However, the modified dice and deck systems that I've described exist somewhere in between the two poles, and it isn't easy to decide between them just by thinking about them in the abstract. Thankfully, there are mathematical tools that can help us analyze and compare these two systems.

There are two properties of each system that we need to be able to measure: predictability and fairness.

To measure the predictability of a system, we can look at the system's average entropy). The entropy of a probability distribution is a measurement of how unpredictable the distribution is. Entropy is maximized when a distribution is uniform, or in other words when all possible values have the same probability, and is minimized when one possible value has 100% probability and the rest have 0%. The systems that we are analyzing use probability distributions that change over time, so to measure a system's unpredictability we can track the average entropy of the distributions over many samples.

When measuring the fairness of a system, we say that a system is fair when all possible values are chosen a similar number of times. The more similar the number of times that each possible value is chosen, the more fair the system is. To measure this, we can calculate the variance of the number of times each value is chosen (I'll call this measure the “outcome variance"). This measurement will be minimized when every value is chosen the same number of times, and maximized when a single value is chosen exclusively.

The Generalized Deck and Dynamic Dice Systems

To properly analyze the two systems in detail, we'll have to define them more explicitly. I'll call the modified version of the deck system the “generalized deck" system, and the modified version of the dice system “dynamic dice".

The generalized deck system is defined by two parameters, aside from the number of values that it can output: The “size factor", which is the number of copies of each value that are inserted when filling the deck, and the “refill constant", which is the minimum number of values allowed to be in the deck before the deck will be refilled. Each parameter must be an integer greater than or equal to 1.

The dynamic dice system is defined by just one extra parameters, aside from the number of possible values that it can output: The “decrease factor", which determines the amount by which a value's probability decreases once it is chosen. The decrease factor must be a real number greater than 0 and less than or equal to 1. After a sample is taken, the chosen value's probability will be set to the product of the value's old probability and the decrease factor. Then, all probabilities will increase in such a way that the total probability still sums to 1, and the proportions between all the probabilities remain the same.

Comparing the systems

It is not straightforward to figure out how much each of the two properties, fairness and unpredictability, is worth. For instance, how much is an increase in fairness worth, in terms of how much unpredictability it costs? That question is outside the scope of this article, so in the following analysis I will assume that there is some fixed level of unpredictability that a designer wants, and attempt to find which system can be the fairest while still achieving that level of unpredictability.

For any given number of possible values, the probability distribution over those values with the highest entropy will be the uniform distribution, which is what the dice system uses. This is why the dice system is the least predictable randomness system possible. So, every randomness system will have entropy that is less than or equal to the entropy of a dice system with the same number of possible values. Systems with different numbers of possible values will have different maximum entropies, so to measure entropy in a standard way, we can measure the entropy of a system as a fraction of the entropy that a dice system with the same number of possible values would have (this will always be a number between 0 and 1, since no system can possibly have more entropy than the dice system).

Say we decided that we wanted our randomness system to be at least 90% as unpredictable as the dice system, on average. This would mean that we want the entropy of the probability distributions used by the system to be, on average, at least 90% of the entropy that a uniform distribution would have.

Once we have decided what level of unpredictability we want, the number of possible values the system should output, and the number of samples over which we wish to measure the system, we can search the parameter-space for the ideal version of each system (generalized deck and dynamic dice). We can do this by defining the sets of parameters we want to search for each type of system, and then measuring the average entropy and outcome variance over the given number of samples for the system defined by each set of parameters. We can then compare the best examples of each type of system.

For example, say we want a randomness system with 6 possible output values, and we want it to be at least 90% as unpredictable as a dice system over a period of 25 samples. Which type of system, generalized deck or dynamic dice, can give us the best results here, and what are the ideal parameters to use? We can figure this out by checking a bunch of different versions of each type of system, using different parameters for each version. For the dynamic dice system, we could come up with, say, 100 uniformly distributed numbers between 0 and 1 to use for the decrease factor, and for the generalized deck we could check all combinations of parameters where the size factor and refill constant were less than, say 10. For each of these sets of parameters, we define a system with 6 possible output values, and measure it's entropy and outcome variance over 25 samples. Then, we select the version of each type of system that has the lowest outcome variance while still being above the 90% threshold.

The Results

I have written some code to run the testing process I described in the last section. Here's a link to the github repository. Running that code with the constants I suggest above (6 possible output values, 90% entropy threshold, and 25 samples), we find that the best generalized deck system has a size factor of 1 and a refill constant of 6, while the best dynamic dice system has a decrease factor of 0.355. The outcome variances of the two systems, run over 25 samples, are 0.51 and 0.46, respectively. In this case, the dynamic dice system is the clear winner.

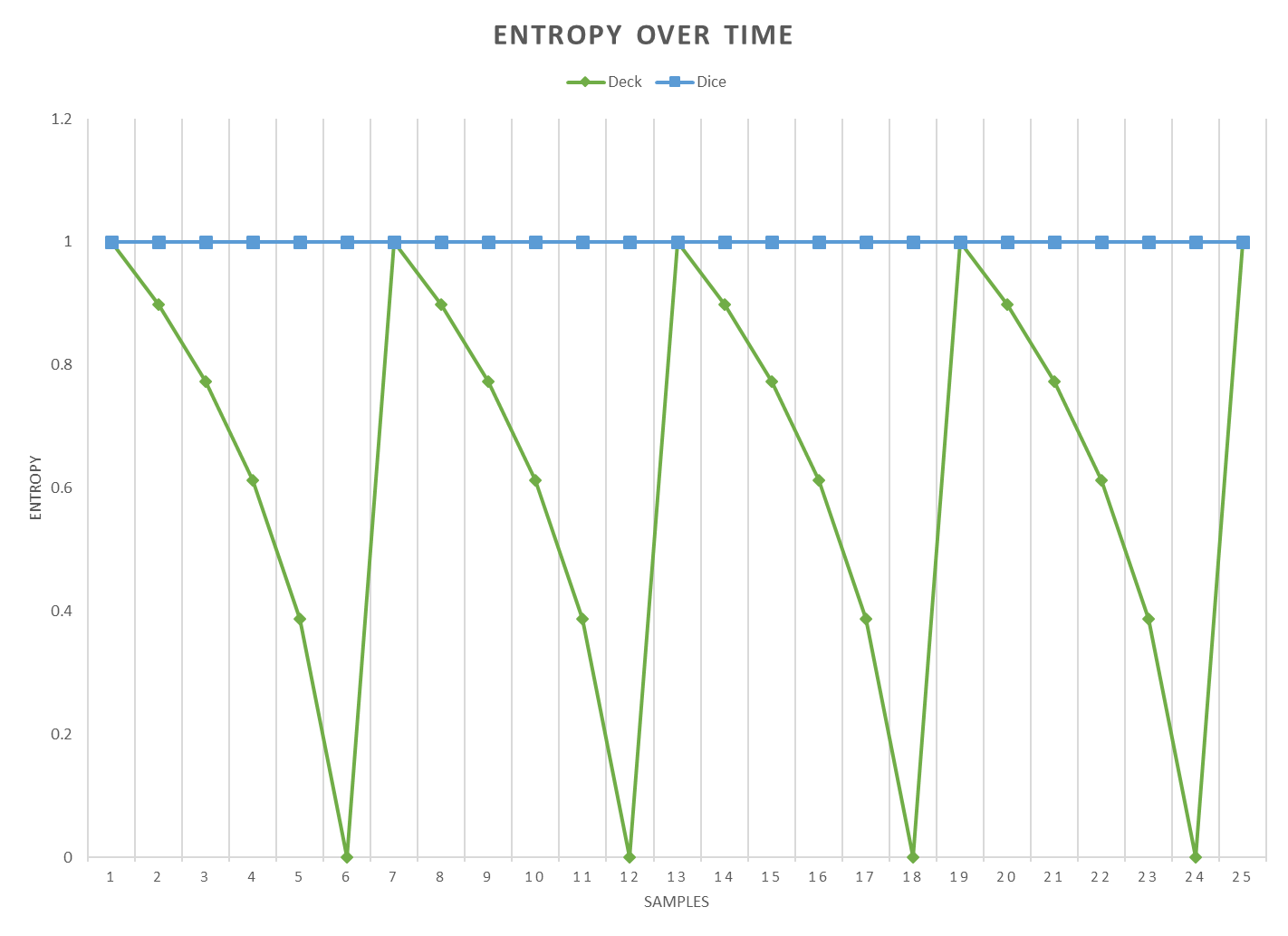

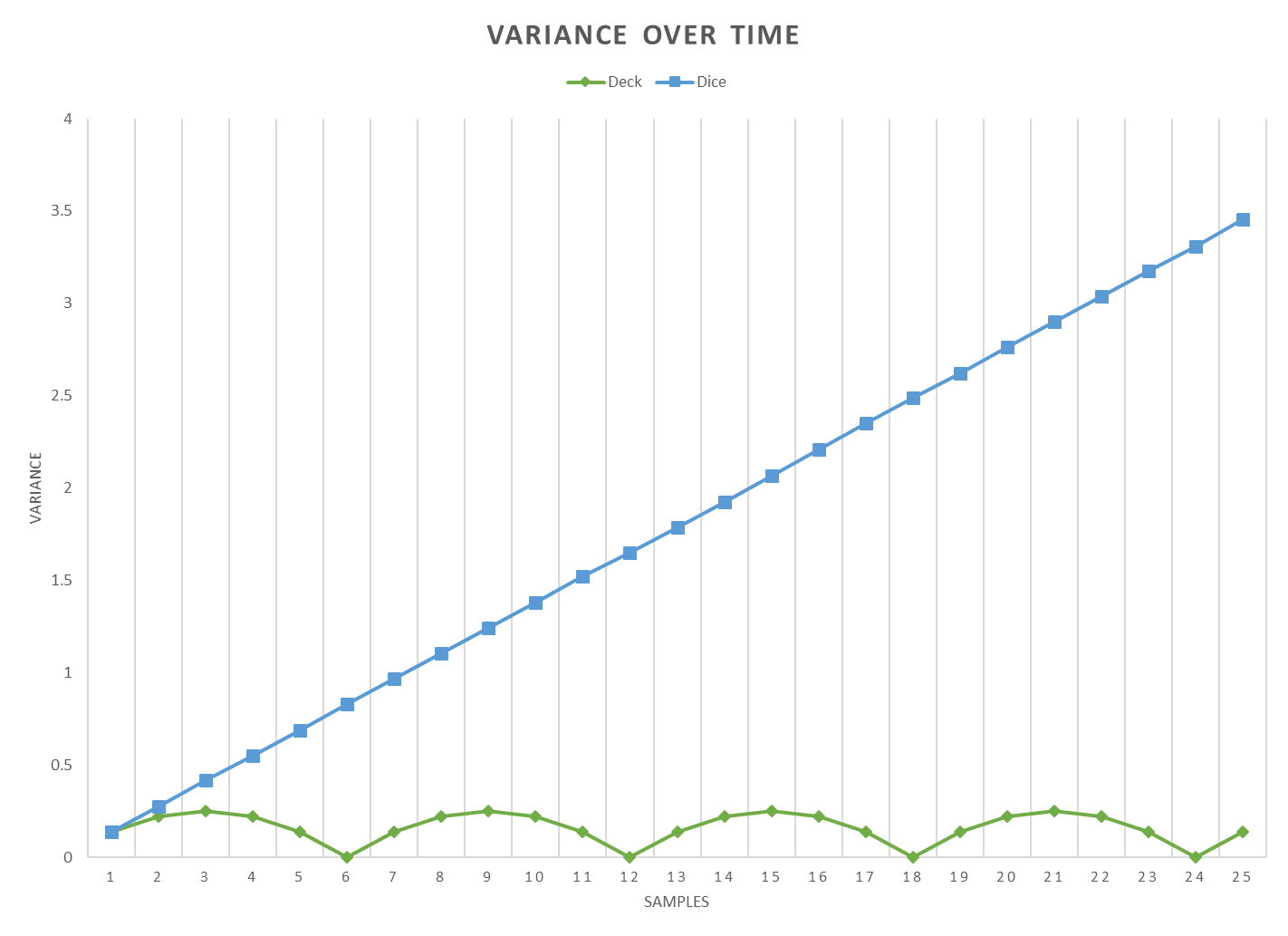

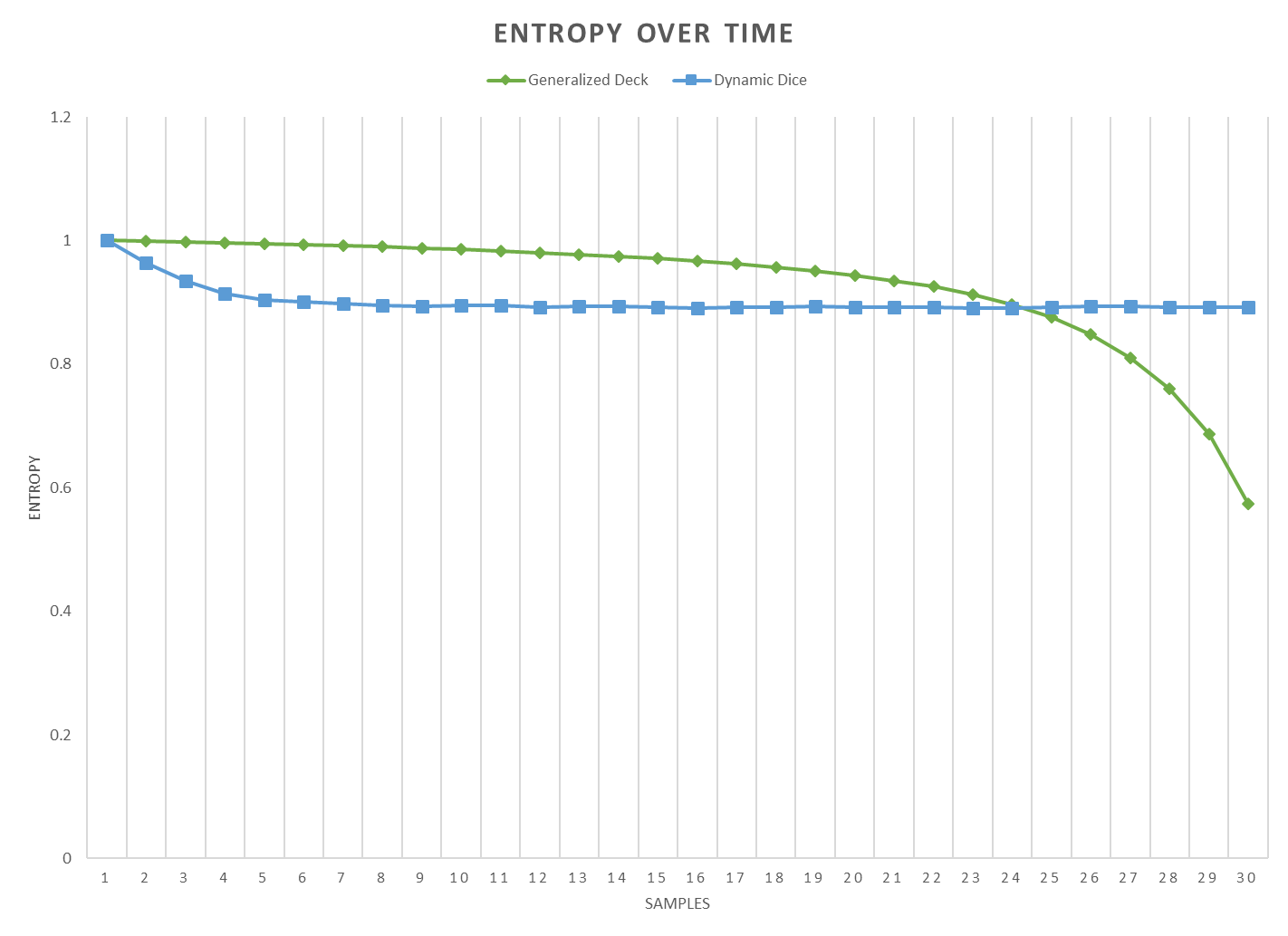

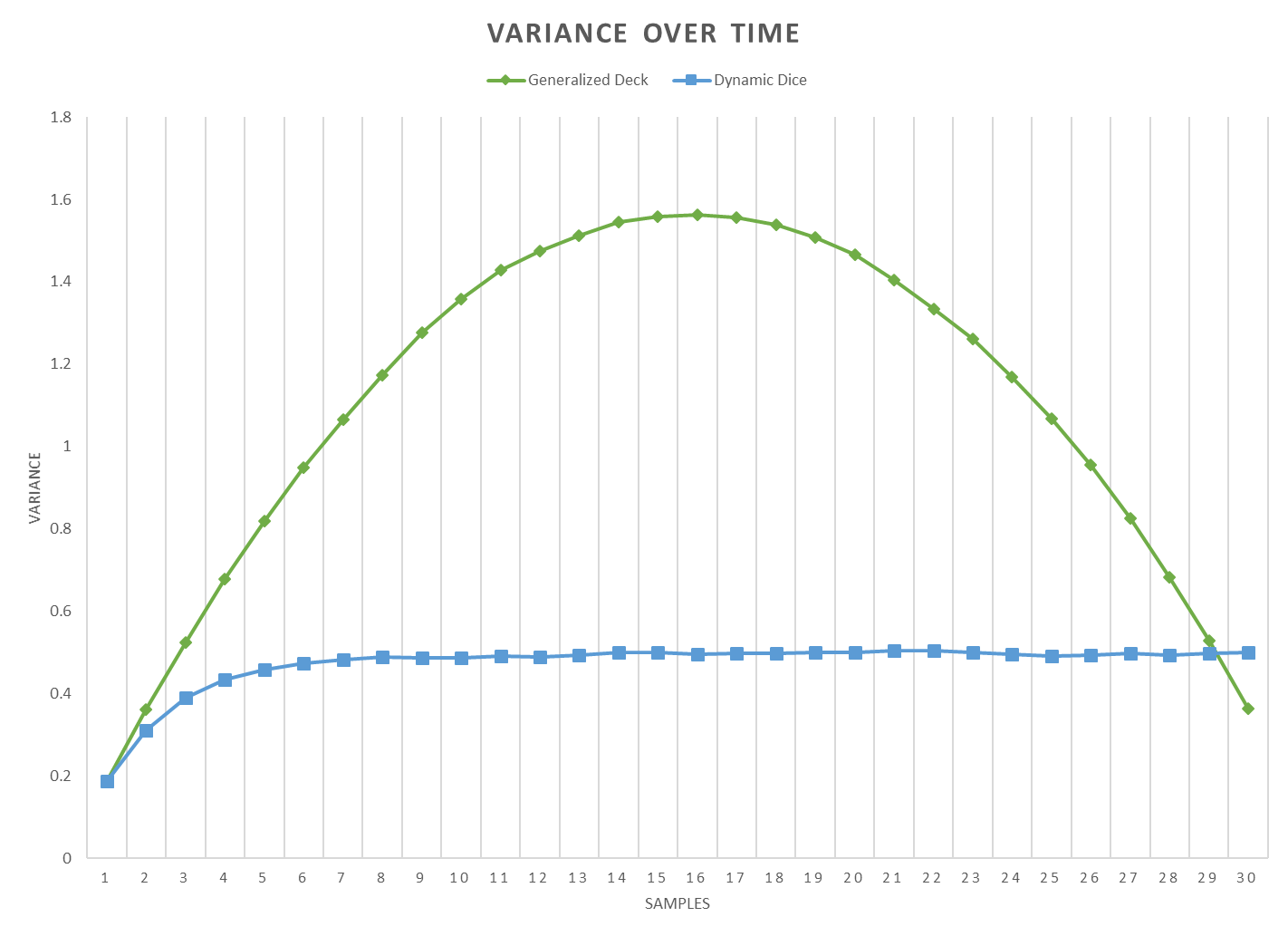

Looking at the graphs of the two system's entropy and variance over time can give more insight about how they differ. First I'll show some graphs comparing normal deck and dice systems, which show the entropy and variance with 6 possible values over 25 samples:

As we can see, the deck system maintains a quite low level of variance, but it's entropy is often very low. Both the variance and the entropy go through phases, which correspond to the deck emptying and refilling. The dice system, on the other hand, has maximal entropy at all times, but it's variance increases with time.

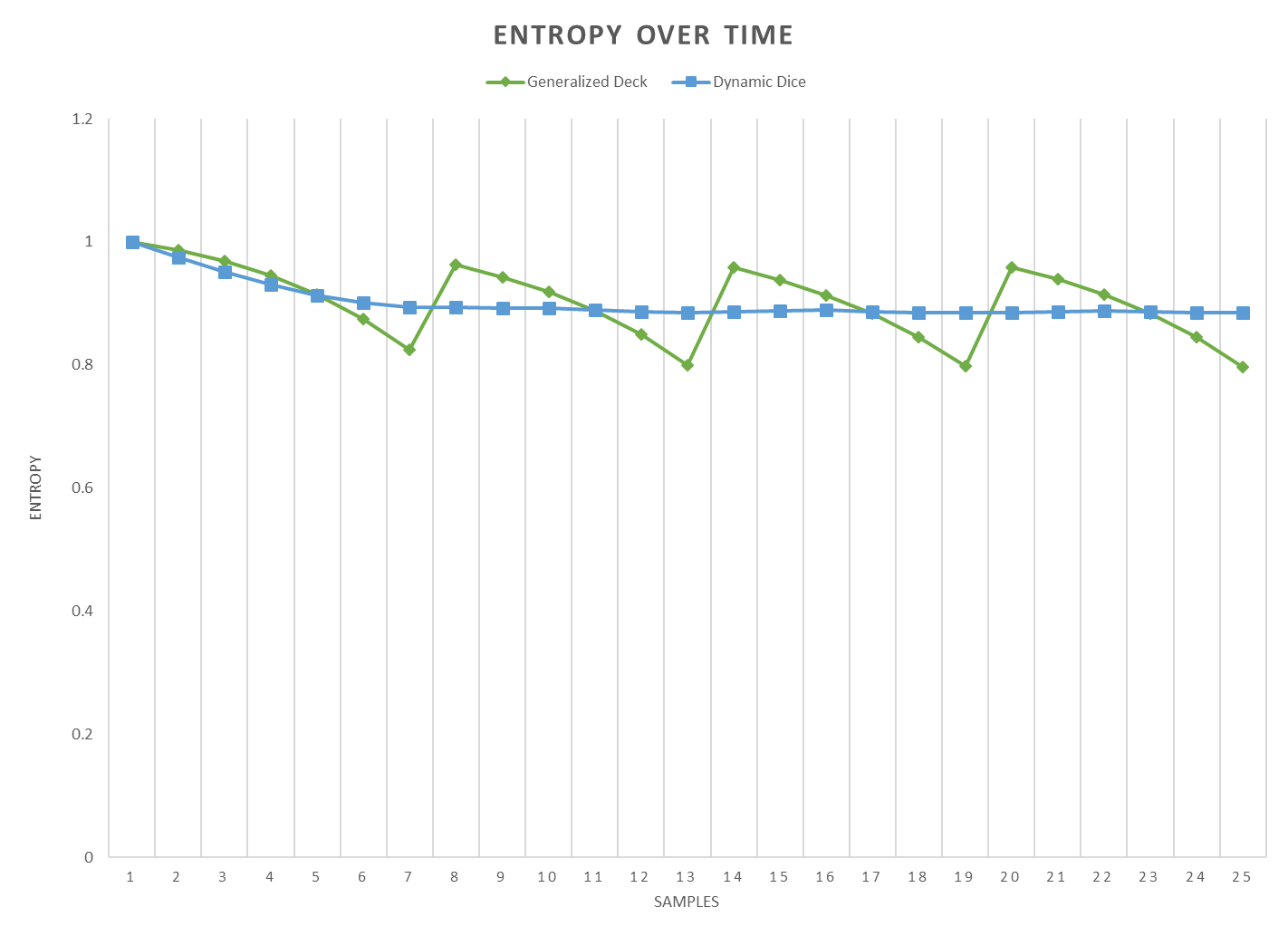

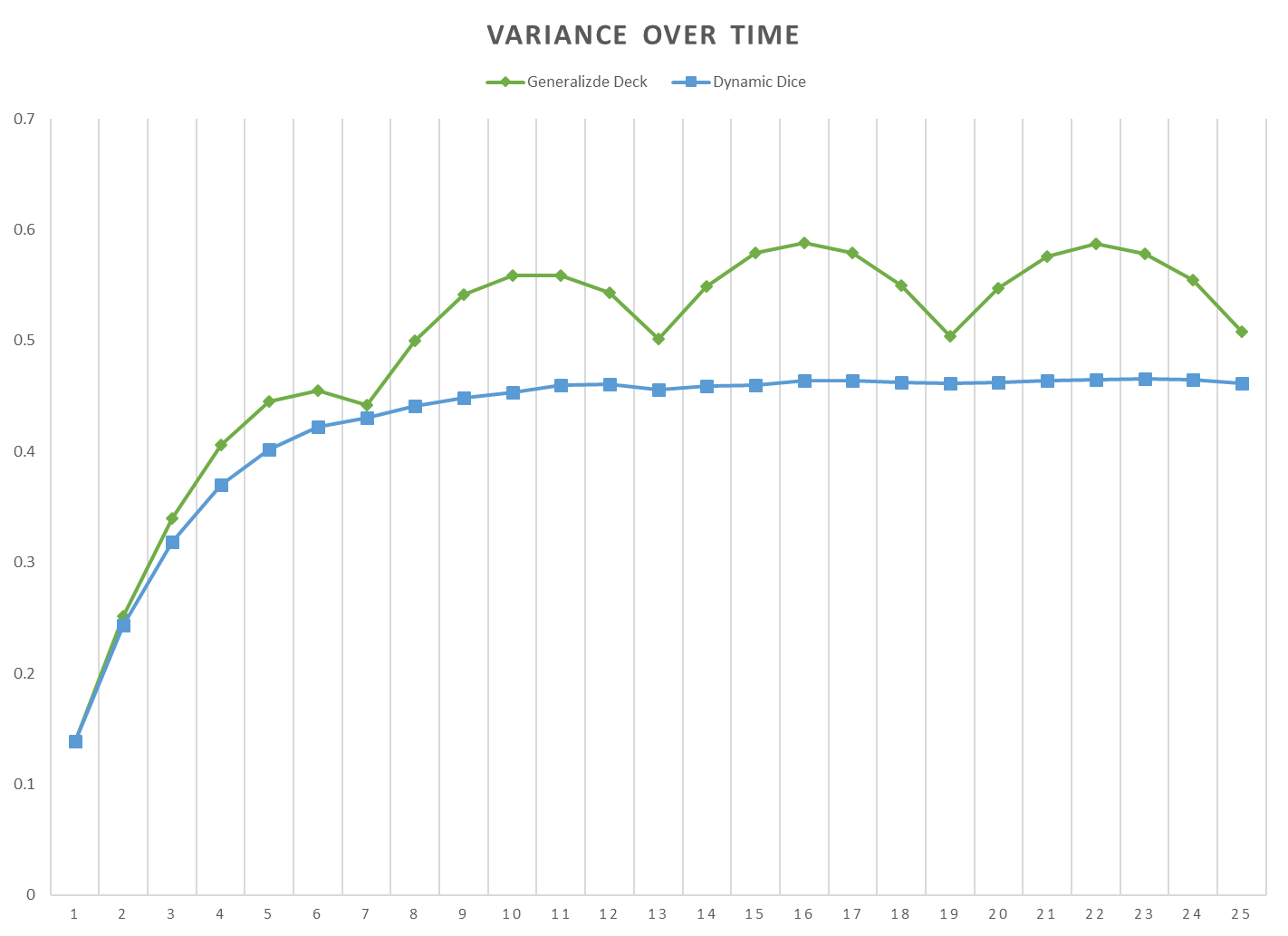

Now let's look at the same graphs the ideal versions of each system, a generalized deck with a size factor of 1 and a refill constant of 6 and a dynamic dice with a decrease factor of 0.355:

These graphs show that the generalized deck system, just like the unmodified deck system we looked at before, goes through cycles in its levels of entropy and outcome variance. The dynamic dice system, on the other hand, reaches a stable level of entropy and outcome variance after about 10 samples.

The parameters we found for this situation will not necessarily be the best parameters in all situations. For instance, if we wanted our systems to be above an entropy threshold of 95% instead of 90%, the parameters we used wouldn't be up to par. Or, if we wanted a different number of possible values in each system, or wanted to take a different number of samples, the ideal parameters may change. There may even be situations where the generalized deck performs better than the dynamic dice.

For instance, if we instead wanted 4 possible output value and we wanted to take 30 samples, while still having at least 90% entropy, the ideal parameters for the generalized deck system are 8 for the size factor and 1 for the refill constant, while the ideal decrease factor for the dynamic dice system is 0.425. The outcome variances are 0.36 and 0.50, respectively, so the generalized deck is the best system here by far, unlike the previous scenario. Let's look at the graphs of these two systems:

The lines showing the dynamic dice's entropy and outcome variance look similar to the last trial, but the generalized deck's lines look very different. Instead of going through repeated cycles, the generalized deck's outcome variance goes through one long arc, being very high near the middle, after about 15 samples, but getting very low at the end, after 30 samples. This is because the size factor used here was 8, which means that the deck contained 8 copies of each of the 4 possible output values, so 32 values in total. Since the refill constant was 1, the deck won't refill until it's entirely empty, which means that the deck will choose all possible output values exactly 8 times after 32 samples. Here we measured over 30 samples, so the deck is very close to having gone through all of its contents, which means that it has very low outcome variance, but also low entropy. After the 32nd sample, the pattern of entropy and outcome variance would begin a new cycle.

While the generalized deck system with a size factor of 8 and a refill constant of 1 was significantly better than the dice system in the exact scenario we tested, it would not fair as well if we hadn't taken 30 samples. For instance, if we had instead taken 29 samples, the generalized deck would have had slightly more variance than the dynamic dice, as can be seen on the graph. And if we had taken 28 or fewer samples, the dynamic dice would have been significantly better. Similarly, if we had gone on to about 35 or more samples, the dynamic dice would have also been superior. The generalized deck system with a size factor of 8 has very low variance when it is near the beginning or end of one of it's samples, or in other words when the number of samples is around a multiple of 32, but otherwise it has quite high variance.

In most games, the number of samples that happens in a particular match won't be perfectly consistent, and instead different numbers of samples will be taken in different matches. This is not a problem for the dynamic dice system which, as we can see in the graphs above, has very consistent entropy and variance regardless of the number of samples taken, but the entropy and variance of the generalized deck vary wildly depending on the number of samples taken. This means that, while the generalized deck system can be shown to be superior in very specific circumstances, the dynamic dice system will perform better on average when there is uncertainty about the number of samples being taken.

Conclusion

The deck system and the dice system represent the poles of the fairness/unpredictability tradeoff. The dice system is maximally unpredictable but very unfair, while the deck system is maximally fair but very predictable. There are many possible systems that lie somewhere between these two poles, and I've explored the properties of two such systems: 1) the dynamic dice system, in which each possible value is assigned a probability, and each value's probability is adjusted downward whenever it's chosen, and 2) the generalized deck system, which uses a deck with some number of multiples of each possible value, and which refills the deck when it is nearly empty.

Each system is better in some scenarios, but the dynamic dice system is more robust in the face of uncertainty about the number of samples being taken, so I think it is the better system to use in most games. However, it may not be the best for all games, and even once you've decided which system to use, you need to figure out which parameters to use. Thankfully, the code I've written can be used to figure out the ideal parameters for both systems depending on how many possible values you want the system to have, how many samples you plan to take from the system, and how uncertain you want the system to be. So, if you are designing a game, and you want to find the best randomness system to use, you can use the program I've written to search for the best system and parameters to use in your game.

Tags: Game Design